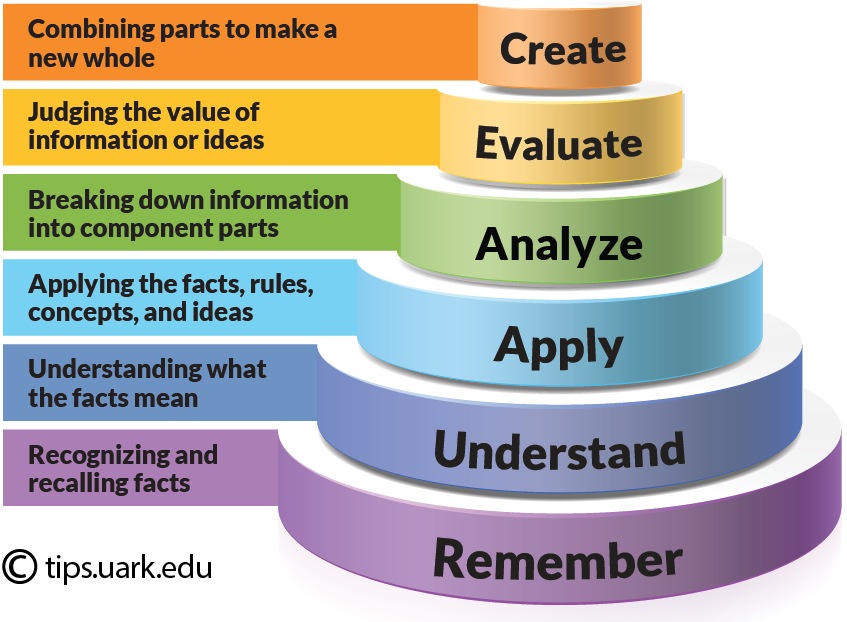

Bloom’s Taxonomy, (in full: ‘Bloom’s Taxonomy of Learning Domains’, or strictly speaking: Bloom’s ‘Taxonomy Of Educational Objectives’) was initially (the first part) published in 1956 under the leadership of American academic and educational expert Dr Benjamin S Bloom. ‘Bloom’s Taxonomy’ was originally created in and for an academic context, (the development commencing in 1948), when Benjamin Bloom chaired a committee of educational psychologists, based in American education, whose aim was to develop a system of categories of learning behaviour to assist in the design and assessment of educational learning.

EXPLANATION OF BLOOM’S TAXONOMY

Taxonomy means ‘a set of classification principles’, or ‘structure’, and Domain simply means ‘category’. Bloom’s Taxonomy underpins the classical ‘Knowledge, Attitude, Skills’ structure of learning method and evaluation, Bloom’s Taxonomy of Learning Domains remains the most widely used system of its kind in education particularly, and also industry and corporate training. It’s easy to see why, because it is such a simple, clear and effective model, both for explanation and application of learning objectives, teaching and training methods, and measurement of learning outcomes.

Bloom’s Taxonomy provides an excellent structure for planning, designing, assessing and evaluating training and learning effectiveness. The model also serves as a sort of checklist, by which you can ensure that training is planned to deliver all the necessary development for students, trainees or learners, and a template by which you can assess the validity and coverage of any existing training, be it a course, a curriculum, or an entire training and development programme for a large organisation.

BLOOM’S TAXONOMY DEFINITIONS

Bloom’s Taxonomy model is in three parts.

1. Cognitive domain: Deals with the intellectual capability, i.e., knowledge, or ‘think’.

2. Affective domain: Looks at the feelings, emotions and behaviour, i.e., attitude, or ‘feel’.

3. Psychomotor domain: Deals with movements, Manual and physical skills, i.e., skills, or ‘do’.

In each of the three domains Bloom’s Taxonomy is based on the premise that the categories are ordered in degree of difficulty.

An important premise of Bloom’s Taxonomy is that each category (or ‘level’) must be mastered before progressing to the next. As such the categories within each domain are levels of learning development, and these levels increase in difficulty. The learner should benefit from development of knowledge and intellect (Cognitive

Domain); attitude and beliefs (Affective Domain); and the ability to put physical and bodily skills into effect - to act (Psychomotor Domain).

BLOOM’S TAXONOMY OVERVIEW

Here’s a really simple adapted ‘at-a-glance’ representation of Bloom’s Taxonomy. This simple overview can help you (and others) to understand and explain the taxonomy. This overview helps to clarify and distinguish the levels. For the more precise original Bloom Taxonomy terminology and definitions see the more detailed domain structures beneath this at-a-glance model. It’s helpful at this point to consider also the ‘conscious competence’ learning stages model, which provides a useful perspective for all three domains, and the concept of developing competence by stages in sequence.

Cognitive Affective Psychomotor Knowledge Attitude Skills

1. Recall data 1. Receive (awareness) 1. Imitation (copy)

2. Comprehend/Understand 2. Respond (react) 2. Manipulation (follow instructions)

3. Apply (use)

3. Value (understand and act) 3. Develop Precision

4. Analyse (structure/elements)

4. Organise personal value system

4. Articulation (combine, integrate related skills)

5. Synthesize (create/build)

5. Naturalization (automate, become expert)

6. Evaluate (assess, judge in relational terms)

5. Internalize value system (adopt behaviour)

(Feed generated with FetchRSS)

(Feed generated with FetchRSS)

INTRODUCTION

Violent conflict escalated in Africa in 2014, with five sub-Saharan states - the Central African Republic (CAR), Nigeria, Somalia, South Sudan and Sudan - accounting for an estimated 75% of all conflict-related deaths on the continent. This unit aims to introduce learners to the state of conflict in Africa through history up to the present, following certain discernable phases. It will focus particularly on the present stage of conflict in Africa, starting with the end of the Cold War. It will assist learners to gain and deep understanding of the nature and causes of modern conflict in Africa. Some brief case studies of major conflicts in Africa are also provided as reference points.

PRE-COLONIAL HISTORY

The history of Africa as a continent is replete with conflict. (Alabi, 2006:41). One may even assert that the major current that runs through Africa: from North to South, East to West and Central is conflict and wars. Since the 1960’s, series of civil wars had taken place in Africa. Examples include: Sudan (1995-1990), Chad (1965-85), Angola since 1974, Liberia (1980- 2003), Nigeria (1967-70), Somalia (1999-93) and Burundi, Rwanda and Sierra Leone (1991-2001). The continent of Africa has been highly susceptible to intra and inter- state wars and conflicts. This has prompted the insinuation that Africa is the home of wars and instability. Most pathetic about these conflagrations is that they have defied any meaningful solution and their negative impacts have retarded growth and development in Africa while an end to them seems obscure. The military history of Northern Africa was closely intertwined with that of its neighbours bordering on the Mediterranean Sea. Egypt was one of The four. major sites of the rise of civilizations in its own right, dominating the region arid maintaining its own standing army. Carthage (in modern-day Tunisia) battled for centuries with the Greeks, and Alexander the Great went on to conquer Egypt. Rome, however, began to emerge as the dominant power in the Mediterranean, conquering North Africa in 146 BC. Following the decline of the Roman Empire Arab armies began conquering much of Northern Africa, which eventually came under the nominal control of the Ottoman Empire, although powerful independent states, such as Morocco, did emerge.

Sub-Saharan Africa, on the other hand, was largely isolated from the northern ancient civilisations by the Sahara Desert. Settlers began spreading down the Rift Valley from Ethiopia and the introduction of the camel from Asia around 100 BC allowed the expansion of trade routes across the Sahara. These developments saw the movement of iron tools and weapons into sub-Saharan Africa. This was one of the triggers for the colonization and development of much of southern Africa by Bantu-speaking peoples from Nigeria over the first millennium AD. Powerful Bantu states began to emerge in the second millennium AD, such as the Great Zimbabwe, the Congo, and the Lunda. Ethiopia also emerged as a powerful independent Christian state, despite being largely surrounded by the influence of Islam. Arab traders and colonists also established their presence in East Africa following Indian Ocean trade routes.

Conflict at this point was largely related to the expansion of dominant states and small-scale conflicts between pastoralists and agriculturalists over access to resources. The emergence of the slave trade first by the Arabs, and later by the Europeans (first the Portuguese, but later the Dutch, English and the French) brought about major changes to the nature of conflict in Africa. African communities did practice slavery prior to the arrival of foreign slave traders, but the slaves were mainly prisoners from intertribal conflict, and many were eventually integrated. The external slave trade, however, saw the acquisition of slaves for sale as a cause of conflict, with dominant states and tribes attacking their neighbours for the purpose of capturing as many slaves as possible which would be sold to the Arab and European slave traders based in coastal forts.

The Colonial Era

The 1800s saw the first major move by foreign powers to enter and dominate the African interior, spurred largely by the demand for resources and markets created by the industrialisation process in Europe. European powers began pushing further inland, beginning with the Dutch settlers in Cape Colony and the French in Algeria. This process intensified in the late 1800s, with the British invading parts of western (primarily Nigeria), northern (Egypt and the Sudan), eastern (Kenya and Uganda) and southern (from Cape Colony through to

Rhodesia) Africa, the French colonising large parts of northern and Western Africa, and the Portuguese taking over Mozambique and Angola. Other European countries joined in what became known as the 'Scramble for Africa', including Italy (Libya, Somaliland and Eritrea), Belgium (Congo), Germany (East Africa, South West Africa and Cameroon.

Violence associated with the process of colonisation and the numerous organised resistance movements that broke out in response to colonisation dominated conflict in Africa from the late 1800s onwards, in many areas until their independence. King Leopold's (Belgium) colonisation of the Congo was particularly brutal, and is thought to have resulted in as many as 10 million deaths between 1880 and 1920 — half of the entire population. Only Liberia (which had already in effect been colonised by freed American slaves and by the American Firestone Company). and Ethiopia maintained some form of independence. The First World War had some impact on Africa, with soldiers brought to Europe to fight on behalf of their colonial masters, and African colonies becoming staging grounds for proxy clashes. The defeat of Germany saw its colonies transferred to the control of neighbouring colonial powers.

Independence and the Cold War

The Second World War showed that colonialism was no longer tenable. French military defeat to Germany and British defeats to a non-white enemy (Japan) made it difficult for the colonial powers to reassert control and return to ‘business as usual’ after the war. Independence in most cases was a somewhat rushed affair, and preparations for self-rule by the colonial powers were hopelessly inadequate. Infrastructure was poor, and indigenous Africans had been almost entirely denied tertiary education and positions of responsibility in the colonial government. The fact that borders had originally been drawn without any regard for ethnic or linguistic identities also contributed to a crisis of legitimacy for the newly installed governments in many newly independent states. Furthermore, just as the European colonists had exploited the colonies, many of the new indigenous rulers continued the practice, following patronage politics and blurring the line between public and personal benefit. Repressive dictatorships

continued to dominate African politics for the following decades, and it was not until 1991 that an incumbent president was defeated at the polls (first in Benin).

All of these were contributing factors in the violence in Africa in the decades following independence. Breakaway attempts by southern Sudan (Sudan), Biafra (Nigeria), Katanga (Congo) and Eritrea (Ethiopia) resulted in major civil wars. On top of these internal factors, the Cold War cast a large shadow over the continent, as the USA and USSR battled for influence in Africa. In this sense, the term 'Cold War' is somewhat misleading, for although direct conflict between the two superpowers did not occur, numerous 'hot' proxy wars did occur in Africa and elsewhere. Each found (or installed) allies in power and supported them with weapons, loans and other support regardless of how corrupt or repressive they were.

US support for Mobutu Sese-Seko in Zaire, and Soviet support for Mengistu Haile Mariam in Ethiopia are key examples. Where a government perceived to be hostile was in power, the superpower would often militarily and financially support rebel groups, perpetuating civil war. In Angola, for example, the USA supported the rebel group UNITA against the Soviet-backed government. Cold War politics also overlapped with the apartheid politics of the regional power, South Africa, which affected the conflicts in Mozambique, Angola, Namibia and Zimbabwe. The end of the Cold War at the end of the 1980s was to change all this. The Soviet Union collapsed together with the intense superpower rivalry that had

gripped the world for more than 40 years. The political importance that the USA and the former Soviet Union had attached to Africa began to disappear. Governments and rebel movements alike found themselves of being unable to access resources and support from their former patron super- powers. This led to changes in the nature of conflict that continue to this day.

1. What feature of the transition to independence let to conflict in Africa?

(Feed generated with FetchRSS)

Introduction

We tend to think of the landscape as unchanging. However, it is slowly and continuously being reshaped. Usually, this reshaping of the landscape results into the production of soils. Soil is formed from the break-down of the parent materials by the process known as weathering. This is the result of climatic factors such as wind, water, temperature and sunshine. It is also due to action by chemicals. In this section, we shall discuss the various types of weathering processes.

3.1.1 WEATHERING

Exposure to wind, rain and frost causes rocks to break apart and crumble. This is known as weathering. There are two main types of weathering: physical and chemical.

1. Physical weathering

Physical weathering includes the actions of wind, water and temperature. Rain water can collect in cracks in the rocks and freeze as the temperature drops. This causes expansion as the ice forms, forcing the crack apart. When the temperature rises, the ice melts, and again water fills the crack. This process of freeze-thaw weathering can be repeated over time, making the crack steadily wider until a boulder falls. Temperature changes also produce stresses in the rock because the different minerals present expand (in hot sunshine during the day) and contract (in the shade and at night) at different rates. Rocks and boulders will detach from a slope, causing scree.

Figure 3.7: weathering process (Copyrights belongs to the owner of the image)

As seen above, in physical weathering the agents are: water, wind, temperature changes and ice.

Water: Running water carries away loose particle of rocks of different sizes and deposits them elsewhere. As the rock fragments are carried, they constantly rub against each other and the ground of the river bed. This wears away the ground and also the fragments themselves which become smaller.

Wind: Wind carries away dust particles, which are blown against rock surfaces, causing them to wear away. Frequently, wind removes loose material leaving the rock exposed to further weathering.

Temperature: Temperature changes can cause the expansion (on heating) and contraction (on cooling) of the various minerals, which the rock consists. Each of the minerals expands and contracts at different rates of different amounts according to their physical properties. This causes fractures to occur in the parent materials, which over a long period of time disintegrates.

Ice: As the temperature reach freezing point, water in the crevices and cracks of rocks freezes. The force of expansion of the ice causes the rock to crack further the shatter. When the temperature rises again, the ice melts and the pieces of rock shattered by the ice are carried away by the melting Ice. The movement of these pieces of rock causes further disintegration.

2. Chemical weathering

Natural rain water contains dissolved carbon dioxide and is therefore slightly acidic. This rain ‘water will very slowly dissolve rocks such as limestone:

limestone + rain water → calcium hydrogencarbonate

CaC03(s) + H20(1) + C02(aq) → Ca(HC03)2(aq)

This process will be increased by ‘acid rain’, which contains dissolved pollutants such as sulphur dioxide and oxides of nitrogen. Some minerals take up water and become hydrated. This causes expansion, and therefore stress, in rock formations. Fragments of rock are again broken off.

The material broken from rock structures by weathering can then be carried away by erosion.

Both the physical and chemical weathering, can be initiated by living organisms either in search for food or habitation (shelter). This form of weathering is sometimes referred to as biological weathering.

3. BIOLOGICAL WEATHERING

Plants and soil organisms also cause weathering. Plant roots grow into minute cracks in rocks and the chemical they produce result in some breakdown of the rocks.

Soil organisms such as termites, earth warms and bacteria have a considerable effect on soil formation.

3.1.2 CHARACTERISTICS AND TYPES OF SOIL

One useful product of reshaping the landscape is soil. Soil is formed from fine particles of eroded debris mixed with humus. Humus is decayed organic material from plants and animals. It takes about 400 years to produce 1 cm of soil. Most soils are a mixture of particles of different sizes. They vary in the amounts of salts, water and humus present. The types of soils range from sandy to clay soils.

Soils can be classified according to the proportion of sand, clay and humus which they contain. Thus, a soil containing a large quantity of sand is called sandy soil. A soil containing a large quantity of clay particles is called clay soil. A soil containing a mixture of about one-half sand, one third clay and one sixth humus is known as loamy soil, and it is the most suitable for agriculture.

The proportion of the different sizes of particles in a soil determines the texture of a soil. Soil texture refers to the percentage of composition in a soil of sand, clay and silt particles. A soil in which sand particles predominate shows a coarse texture while a soil in which clay particles predominate has a fine texture. Thus a soil may be termed gravelly, sandy, silt or clayey depending on the proportion of the particular particles in the soil. As different sized particles have different physical properties, the proportion of them in a soil will therefore influence the soil properties; physical and chemical. For example, gravel particles are rather large and also heavy due to their high content of iron. Consequently, gravelly soils contain large spaces between the particles and these spaces allow water to drain off very quickly. Because of this gravelly, soils have very poor water holding capacity (water retention). Such soils are also poor in plant nutrients. By comparison, clay particles exhibit a large surface area and therefore have a considerable greater capacity for holding nutrients and water than either gravel or sand. On soil texture, aeration, drainage, nutrient and water-holding capacity of the soil, depends on penetrability by the roots, etc.

Lastly, the ease of working or cultivating a soil will very much be influenced by its texture. Thus clay soils, having a fine texture, are described as heavy soils and sand soils as light soils. Soil structure is the way the soil particles in a soil are packed. If the soil particles are closely packed, a soil has a solid structure e.g. in a clay soil. If the soil particles are loosely packed, a soil has a loose structure, e.g. in a sandy soil. If the soil particles in a soil appear like the inside of a loaf of bread, then structure is crumb or friable, e. g, in a loam soil.

Table 3.2 Different soil types

| Sandy soils | Loams | Clay soils |

| · large particle size · lack humus · nutrients drain away easily | · ideal for agriculture · sufficient sand for good drainage · sufficient clay to hold nutrients | · small particle size · slow draining · poor aeration |

3.1.3 SOIL PROFILE

Soil profile refers to the arrangement of layers of soil in a profile. This arrangement can only be seen in a dug out pit. It is therefore important for you to carry out practical works to identify the different soil layers. This is because the arrangement of soil, provides a guide in the choice of what crops to grow on a piece of land.

It is important for you to realise that as soil-forming processes continue, the soil develops in depth resulting in the formation of a distinct sequence of soil horizons. A soil horizon is a layer parallel to the soil surface, whose physical characteristics differ from the layers above and beneath. The vertical arrangement of the various soil layers or horizons, are called the soil profile. The different horizons in the profile can easily be seen. The distinct horizons in the profile represent soil layers at different stages of development. Thus, one horizon will differ from the other in one or more properties, e.g. colour, chemical composition, size and the arrangement of the soil particles. Where the soil-forming processes have been active for a long time, then there would be the development of mature, deep soils with a well-developed soil profile, provided there has not been much erosion. Conversely, youthful shallow soils with a poorly developed profile result where erosion has been active and the soil forming processes have not been in action for a long enough. Such a soil will show under decomposed weatherable minerals in its profile. A deep soil having a well-developed profile has great potential for agriculture as it is able to hold more moisture for plant use than a shallow soil

Figure 3.8: Soil ProfileO – Horizon: Organic matter: Litter layer of plant residues in relatively undecomposed form.

A – Horizon: Surface soil/ Topsoil: Layer of mineral soil with most organic matter accumulation and soil life. This layer eluviates (is depleted of) iron, clay, aluminium, organic compounds, and other soluble constituents. When eluviation is pronounced, a lighter coloured "E" subsurface soil horizon is apparent at the base of the "A" horizon. A-horizons may also be the result of a combination of soil bioturbationand surface processes that winnow fine particles from biologically mounded topsoil. In this case, the A-horizon is regarded as a "biomantle".

B – Horizon: Subsoil: This layer accumulates iron, clay, aluminium and organic compounds, a process referred to as illuviation.

C – Horizon: Parent rock: Layer of large unbroken rocks. This layer may accumulate the more soluble compounds .

R – Horizon: bedrock: R horizons denote the layer of partially weathered bedrock at the base of the soil profile. Unlike the above layers, R horizons largely comprise continuous masses (as opposed to boulders) of hard rock that cannot be excavated by hand. Soils formed in situ will exhibit strong similarities to this bedrock layer.

The soil horizons down the profile are named in the following order; the topsoil, subsoil and the substratum. They can also be named respectively as A, B, C and D/R. Of these the topsoil is usually the more fertile, more subject to weathering and cultivation (tillage) operations. The topsoilis also usually better aerated and has therefore the more active soil microorganisms which decompose vegetable matter into organic matter and humus. The topsoil therefore is the horizon in which organic matter accumulates. Further breakdown of the organic matter releases organic acids which react with various mineral constituents in the soil to produce nutrients which are in turn usable by the plants.

The subsoil is usually more compact and less well aerated than the topsoil. An impermeable layer called a ‘hard pan’ may be found in some layers of the subsoil. The hard pan impedes drainage and root penetration and in practice, it has to be broken down by cultivation so as to facilitate water percolation as well as root growth. Sometimes minerals may accumulate in the subsoil as a result of leaching from the topsoil.

Plants are also responsible for moving mineral nutrients from one layer to another through their litter and dead remains. Also involved in this process are various soil- inhabiting organisms, e.g. earthworms and termites. These may interfere with the development of distinct soil horizons by mixing materials from one horizon with another through their various activities, e.g. burrowing, movement, etc. The substratum is also called the bed rock and represents the original soil parent material which is still intact and unweathered.

(Feed generated with FetchRSS)

Introduction

Integrated science processes are complex to children in lower grades, these should be developed to grades 5-7 pupils. They involve other processes of science in order to generate knowledge. The following are examples of integral science processes: hypothesising, experimenting, operational definition, controlling variable and collecting and interpreting data

EXPERIMENTING

Experiments when used in Science, are always associated with practical activity. It is activity undertaken to provide support for one theory, to test a hypothesis and to determine the evidence that may be required to enable alternative interpretations to verify or reject a hypothesis. Effective experiments rely on a wide range of knowledge, understanding and skills.

Experimenting is an essential part of the scientist’s way of operating. Pupils think of practical work as less academically demanding and less like real work” while “some teachers spend more time on it than others. In some cases, engaging in practical work is forced only because it has been demanded by the examination body.

Setting up an experiment requires explicit definition of variables which are for the focus of investigation and the variables which are controlled. The variables may be discrete (integer values), continuous (any value), categorical (specifies characteristics), or derived (obtained by calculation from more than one value). The variables may be defined as dependent (effect/ outcome), independent (experimenter chooses to change systematically, the causative factor), control (controlled to make the experiment results valid) or interacting (arise due to the effects of two or more independent variables). The teacher needs to identify these variables and the appropriate instruments to measure them.

Practical work motivates the pupils to do science and keep them interested. It helps the pupils acquire skills and helps promote logical thinking. Further, it helps the students understand, provides opportunity for them to develop communication skills, provides them the opportunity to work together and learn something from the experience.

In experimenting, at some point, the learners will be introduced to learning basic practical skills and how to use simple measuring instruments. They are also inducted to illustrating laws or principles and proving a theory. At another point, the pupils will be introduced to learning about controlling variables in an investigative work. In this, the teacher is to plan (feasibility, practicalities and safety implications) the experiment, evaluate it and suggest improvements, question their own understanding of scientific phenomena, and search out more information.

Most experiments seek causes and effects and relationships of phenomena. In experimenting, the required equipment and apparatus need to be set in place. The researcher needs to know the type of measurements required (precision), the quantity or readings, and how the records are to be made. The observations are all recorded to lire detail as the experiment proceeds. The experimenter looks for ways of improving data collection. Many experiments can be carried out by children. For young children a problem can be posed for them to investigate by asking questions such as, ‘what would happen if....?’ ‘What is the effect of...?’ These may be of the trial and error kind or they may be well designed investigations.

When carrying experiments, you will be required to use the scientific methods.

The steps of the Scientific Method are:

• Observation/Research

• Analysis

• Hypothesis

• Experimentation

• Conclusion

CONTROLLING AND MANIPULATING VARIABLES

A variable is a quantity, which can take different values during an investigation or experiment. The variables can be discrete, categorical, derived or continuous. There are dependent and independent variables. The control variables are identified and not manipulated during experiments or investigations. The experimenter ought to establish how the control process is to be done.

According to Brook, Driver & Johnson (1989), when an experiment is set up, it requires “explicit definition of the variable or variables which form the focus of investigation and of other variables which need to be controlled” (p.74). The mental models brought to the experiment; experience and the background of the experimenter significantly influence the design as they have a vague idea of the conceptual framework of the experiment. The vague conceptual framework guides the selection of the variables.

According to UNESCO (1985), “The ability to identify and control the variables in an experiment comes with experience, and should be treated at progressive levels of complexity as the child matures” (p.31). The child comes to understand the implications of the process later in their development. By the time they find out about a control variable, they have found more information from other sources. Occasionally, they recognise the vast number of possible control variables. Science instructions need to provide opportunities for the children to relate actual experiences with scientific practices by developing their mental models towards the scientific way. This is done through exploring with them the range and limits of certain models and theories in the course of investigations. They have to be helped to step out of their conceptual framework and to explore other alternative models. The teacher helps the learner to identify the variable to vary and why they consider only one variable at a time.

Example 1

In conducting experiments, we search for cause and effect and their relationships. Consider this situation: Two farmers have twenty hens each. One farmer gets an average of twelve eggs a day but the other one gets an average of six only. There are several factors that could have resulted into this. One factor could be that the second farmer was not feeding the hens on the right kind of feed and another one could be wrong amounts of feed. These factors are called variables. A variable is a quantity which can take different values when carrying out an investigation or experiment. Key variables that define the investigation are two: the independent and dependent variables. The independent variable is the causative factor or effect for which the experiment is intended to explore while the dependent variable is the outcome which is measurable.

For example, in the experiment to show growth of plants, the amount of water would be the independent variable because amounts of water supplied to the plant can be varied while the size of the plant is the dependent variable because its size is dependent on the amount of water supplied. Control variables are the ones that are controlled during the experiment in order to make results valid.

When the effects of two or more independent variables on the dependent variable are not easily separated, they are ‘called ‘interactive variables’, for example, the effect of moisture and air on irons causes rust.

A good investigative activity devised by the teacher for his/her class should help pupils identify dependent and independent variables and how to control variables. They should also be able to pose questions on what they want to experiment and suggest ways of testing their ideas.

HYPOTHESISING

A hypothesis is a statement put forward to attempt to explain some phenomenon. In simple terms it means a reasonable guess to explain a particular event or observation. In science, a hypothesis is made when there is evidence available that can be investigated using scientific principles. Often there could be more than one possible explanation to show that a hypothesis needs to be tested to prove it to be true. Pupils develop the skill of hypothesising if they are able to suggest explanations, which are consistent with the evidence as well as with scientific concepts and theories. Furthermore, if they are able to recognise that there can be more than one explanation for an event and be able to use previous knowledge.

Example 1

Suppose you want to demonstrate a perfect score on an experiment in science. You begin by thinking several ways to accomplish this. You should base possibilities on past observations. If you put each possibility into sentence form, using the words if and then you form a hypothesis.

a. If the science experiment is easy, then I will get a perfect score.

b. If am intelligent, then I will get a perfect score.

c. If I prepare adequately, then I will get a perfect score.

INTERPRETING DATA

The words interpret means “to explain the meaning of something.” Interpreting involves finding a pattern, trend or relationship inherent in a set or collection of data. This data can be presented by: a table, a histogram, or a pie chart.

Young children can present information on a histogram after for example, collecting data on the number of girls and boys in their class. The skill is mostly used by older children who have to present data after an experiment and the interpretation requires a higher cognitive level.

Operational definition is a procedure whereby a concept is defined solely in terms of the operations used to produce and measure it. An operational definition, when applied to data collection, is a clear, concise detailed definition of a measure (measured or derived variable). Since a single word may be used in different contexts taking a different meaning in each situation, definitions provide economy of communication. With the operational definition, the definitions are written in terms of how an object works or how it can be used; that is, what is its job or purpose.

Examples

1. Some operational definitions explain how an object can be used.

a. A ruler is a tool that measures the size of an object.

b. A filter paper is a material used to separate a mixture of soluble and insoluble substances.

2. Other operational definitions may explain how an object works.

a. A ruler contains a series of marks that can be used as a standard when measuring.

A filter paper contains small openings to allow only soluble substances pass through it and trap insoluble mailer as residue

(Feed generated with FetchRSS)

0 Comments